As far as I can remember, it was around 2002. I must have been about eight years old. In our family, reading books beyond the school curriculum was encouraged, and it was from that encouragement that my reading habit developed. Among friends and cousins, there was an unspoken competition—’who had read the most books’. One of my relatives had nearly a thousand books at home.

Mostly, I read storybooks and comics. But around that time, I bought a book titled Stories of Scientists. From that book, I first learned about Marie Curie, Alexander Graham Bell, Alfred Nobel, and others. I think almost every child loves looking at the moon and stars—I was no exception. Perhaps that is why, among the pages of that book, Galileo Galilei stood out to me. He was the first astronomer I ever read about.

To be honest, I am still equally fascinated by him. There was a time when his discoveries, theories, and equations attracted me most. Now, at the age of thirty-two, I find myself even more astonished by his curiosity, perseverance, dedication—and especially his courage. Because I know I am definitely not as brave as Galileo.

Born to a musician father, Galileo initially intended to study medicine at the University of Pisa. Later, encouraged by the mathematician Ostilio Ricci, he turned to mathematics, though he never completed his degree. At just nineteen, he is said to have conducted the famous experiment of dropping objects from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. During his mathematical studies, he became deeply engaged with the works of Archimedes from nearly eighteen centuries earlier than his time. The problem of “Heiro’s Crown” was among the most notable works of him of that time, which later inspired him to design a hydrostatic balance. At only twenty-five, he joined the University of Pisa as a lecturer. Three years later, he moved to the University of Padova as the chair of mathematics. He spent nearly eighteen years there—a period he later described as the “best years of his life”.

It was during this time that he constructed a telescope with 18–20 times magnification. Through it, he demonstrated that the Milky Way was composed of countless stars; he observed the irregular surface of the Moon, the rings of Saturn, sunspots, the phases of Venus, and—most remarkably—the moons orbiting Jupiter. Those moons convinced him that not everything goes around the earth, and the earth may not be the center of everything.

It is believed that from this period onward, Galileo supported Copernicus’s heliocentric model of the solar system. A letter he wrote to Kepler hints at this inclination. In it, he mentioned that he had reflected deeply on Copernicus’s hypothesis and would attempt to find solid evidence in its favor. He also expressed fear that he might suffer the same humiliation and rejection that Copernicus had endured.

For this reason, he refrained for a long time from openly discussing Copernican ideas in his lectures. However, he did engage in conversations about them with close friends. In his view, Copernicus’s mathematics and conceptual framework were far more coherent and logical than the geocentric models of Ptolemy or Aristotle. Even so, he did not immediately advocate the theory publicly—partly because he lacked sufficient proof at the time, and partly because he did not wish to incur the Church’s displeasure. But there are instances where he discussed or even debated these topics without explicitly supporting Copernicus’ ideas, but he always mentioned that the hypothesis has a solid base.

Eventually, however, he could not avoid conflict. A group of hardline Dominican friars began verbally attacking him and accusing him of heresy. Formal complaints were filed against him with the Church. As a result, in 1616, Copernicus’s book was officially banned, and the heliocentric model was declared unacceptable because it contradicted prevailing religious interpretations.

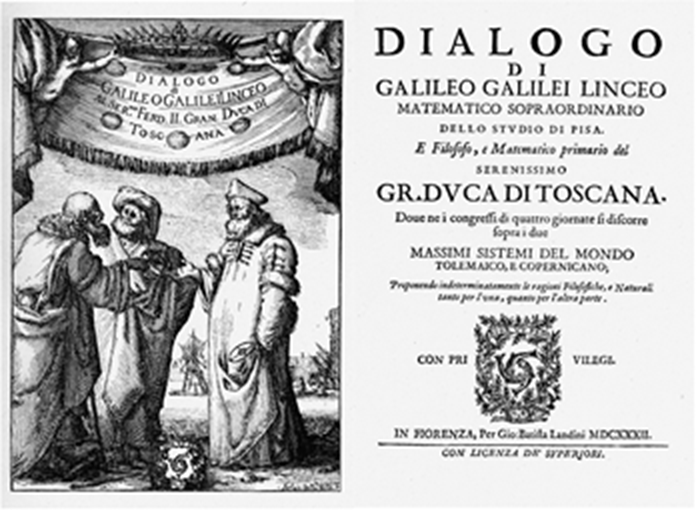

Seven years later, Galileo’s acquaintance Cardinal Maffeo Barberini was elected Pope (Urban VIII). Galileo believed the moment had come to present his views. He wrote his famous Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, where he presented the heliocentric and geocentric models in the form of a structured debate. The book was published in Italian with official Church approval, making it accessible to a broad audience.

Yet after its publication, his fears came true. He was tried for heresy. Ultimately, he was forced to recant his position and was ordered not to advocate heliocentrism. He was sentenced to spend the remainder of his life under house arrest.

Legend has it that after the verdict was delivered, he murmured:

“E pur si muove” — “And yet it moves.”

Whether he actually uttered these words remains historically disputed. The phrase first appeared nearly a century after his death, in a portrait attributed to that later period.

The final years of his life were difficult. He eventually became blind. Yet even under house arrest, he wrote another monumental work—Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences—in which he laid the foundations of kinematics.

Galileo died in 1642. At the time, he was still regarded as a heretic, and he was buried without significant religious or state honors. Four Centuries later, in 1992, the Vatican formally acknowledged that an injustice had been done to him.

Tycho Brahe, through his meticulous observations; Copernicus, through his revolutionary conception of the solar system; and Kepler, through his famous laws, had elevated astronomy from empirical practice to a systematic science. And Galileo—like a true philosopher—reflected deeply on nature’s problems and sought to resolve them through experiment. Most importantly, he demonstrated the courage to stand against the majority. Perhaps he endured great suffering in his own lifetime, but he left behind an enduring example of intellectual integrity and moral bravery for generations to come.

On Galileo’s birthday, I offer him my deepest respect.

References

Galilei, G., & Seeger, R. J. (1966). Galileo Galilei, his life and his works. Oxford.

McMullin, E. (1978). The conception of science in Galileo’s work. New perspectives on Galileo, 209-257

Zanatta, A., Zampieri, F., Basso, C., & Thiene, G. (2017). Galileo Galilei: science vs. faith. Global cardiology science & practice, 2017(2), 10.

Abetti, G. (1931). Galileo Galilei as a Pioneer in the Physical Sciences. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 43(252), 130-144.